I first got into Python in the mid-to-late 1990s. It's so far back that I think the copy of Programming Python that I have (sadly in storage at the moment) might be a first edition. I probably fell out of the habit of using Python some time in the early 2000s (that was when I met Ruby). It was only 22 months ago that I started using Python a lot thanks to a change of employer.

As you might imagine, much had changed in the 15+ years since I'd last written a line of Python in anger. So, early on, I made a point of making Pylint part of my development process. All my projects have a make lint make target. All of my projects lint the code when I push to master in the company GitLab instance. These days I even use flycheck to keep me honest as I write my code; mostly gone are the days where I don't know of problems until I do a make lint.

Leaning on Pylint in the early days of my new position made for a great Python refresher for me. Now, I still lean on it to make sure I don't make daft mistakes.

But...

Pylint and I don't always agree. And that's fine. For example, I really can't stand Pylint's approach to whitespace, and that is a hill I'll happily die on. Ditto the obsession with lines being no more than 80 characters wide (120 should be fine thanks). As such any project's .pylintrc has, as a bare minimum, this:

[FORMAT]

max-line-length=120

[MESSAGES CONTROL]

disable=bad-whitespace

Beyond that though, aside from one or two extras that pertain to particular projects, I'm happy with what Pylint complains about.

There are exceptions though. There are times, simply due to the nature of the code involved, that Pylint's insistence on code purity isn't going to work. That's where I use its inline block disabling feature. It's handy and helps keep things clean (I won't deploy code that doesn't pass 10/10), but there is always this nagging doubt: if I've disabled a warning in the code, am I ever going to come back and revisit it?

To help me think about coming back to such disables now and again, I thought it might be interesting to write a tool that'll show which warnings I disable most. It resulted in this fish abbr:

abbr -g pylintshame "rg --no-messages \"pylint:disable=\" | awk 'BEGIN{FS=\"disable=\";}{print \$2}' | tr \",\" \"\n\" | sort | uniq -c | sort -hr"

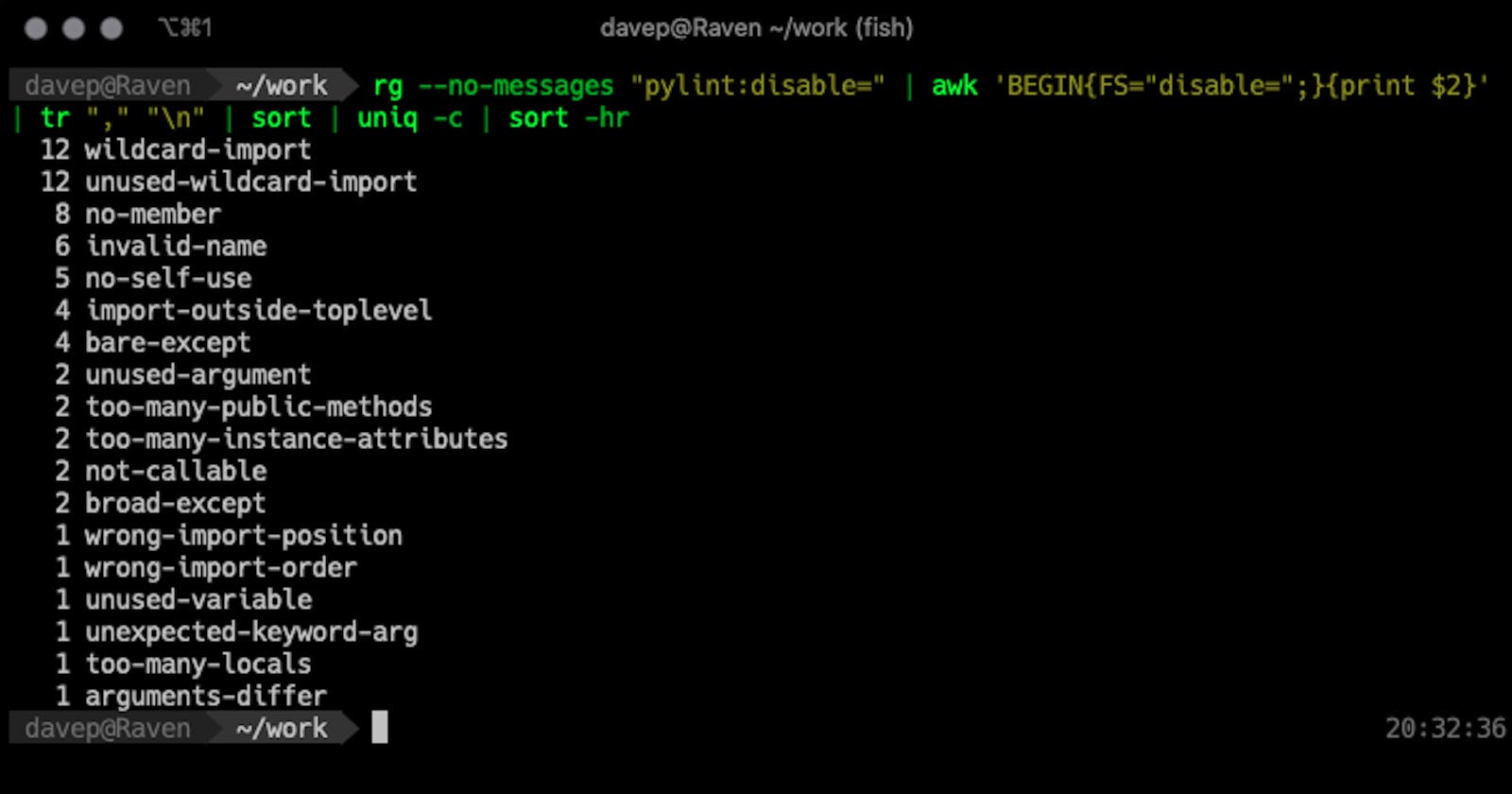

The idea here being that it produces a "Pylint hall of shame", something like this:

12 wildcard-import

12 unused-wildcard-import

8 no-member

6 invalid-name

5 no-self-use

4 import-outside-toplevel

4 bare-except

2 unused-argument

2 too-many-public-methods

2 too-many-instance-attributes

2 not-callable

2 broad-except

1 wrong-import-position

1 wrong-import-order

1 unused-variable

1 unexpected-keyword-arg

1 too-many-locals

1 arguments-differ

To break the pipeline down:

rg --no-messages "pylint:disable="

First off, I use ripgrep (if you don't, you might want to have a good look at it -- I find it amazingly handy) to find everywhere in the code in and below the current directory (the --no-messages switch just stops any file I/O errors that might result from permission issues -- they're not interesting here) that contains a line that has a Pylint block disable (if you tend to format yours differently, you'll need to tweak the regular expression, of course).

I then pipe it through awk:

awk 'BEGIN{FS="disable=";}{print $2}'

so I can lazily extract everything after the disable=.

Next up, because it's a possible list of things that can be disabled, I use tr:

tr "," "\n"

to turn any comma-separated list into multiple lines.

Having got to this point, I sort the list, uniq the result, while prepending a count (-c), and then sort the result again, in reverse and sorting the numbers based on how a human would read the result (-hr).

sort | uniq -c | sort -hr

It's short, sweet and hacky, but does the job quite nicely. From now on, any time I get curious about which disables I'm leaning on too much, I can use this to take stock.